Yunnan’s Sunlight, Wind, Mountains, and Its Nature-Led Cuisine

Author: Zhencheng Zhuang

“Anything familiar in this land can become a page of its own calendar.”

Yunnan is not only a vast kingdom of plants. It may also be one of the most abundant places in the world for land-grown ingredients. From north to south, it draws chefs from all over China who come in search of inspiration throughout the year. In recent years, Yunnan cuisine has become increasingly loved and cherished around China. For many urban diners, it has become a way to taste the feeling of something faraway and exotic. Yet despite such abundance, Yunnan cuisine has never formed a single dominant culinary system. This leads us to wonder: what truly gives a local flavor its lasting life?

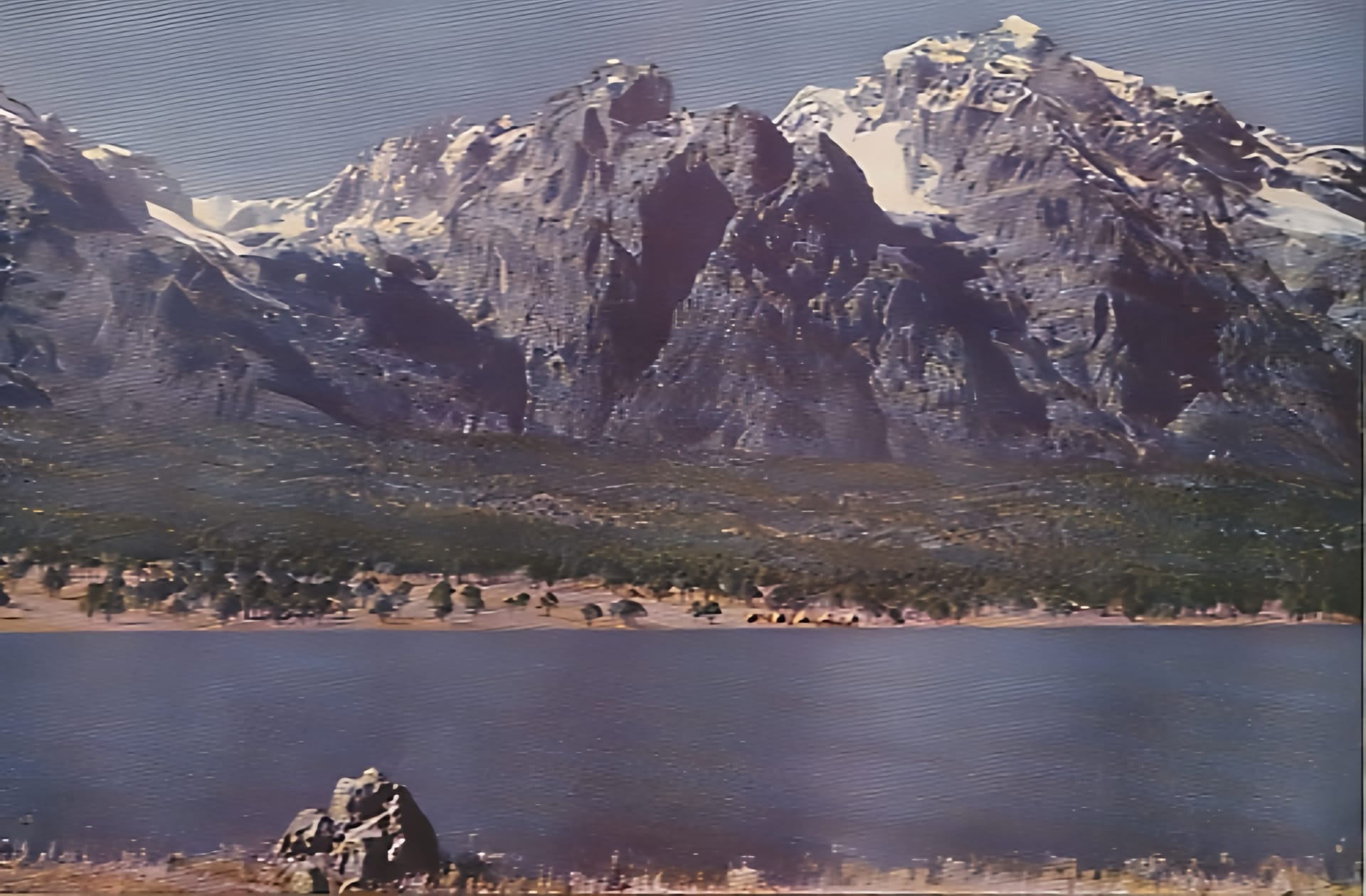

Eating the Mountains

Chef Yang Xuewei is from Dali, Yunnan. He drives his old compact car and takes us from Yanjiao Village toward his home sixteen kilometers away. The highland sunlight pours across the open fields that stretch to the foot of the mountains.

Whenever Yang casually points to a patch of wild grass or a flowering plant growing along the ridge and names it, explains how it is eaten, the Lijiang Basin from Joseph Rock’s writings appears in my mind.

Throughout the afternoon, Yang identifies more than a dozen edible stems, leaves, and fruits from the field edges and the scrubland behind the village. Things a general passerby would take for granted as general vegetation. The wind brushes through the rice stalks carrying a soft rustle. Sunlight rests on every plant and pool of water, giving everything a vivid, breathing glow.

Identifying ingredients is only the first step in “eating the mountains.” Spring brings flowers, summer brings mushrooms, autumn offers fruits, and winter reveals roots. Locals grow up knowing how to recognize seasonal wild plants. This is not textbook knowledge. Their understanding comes from watching branches, observing the color of leaves, and sensing when a plant is at its peak deliciousness. But do not be mistaken, they do not gather only for survival. People in Yunnan understand how to cook with the land and how to transform what the mountains give into genuine flavor.

Catching the Wind

Yunnan is blessed by the monsoon.

In summer and autumn, the monsoon that blows from the Indian Ocean nourishes the mountain forests, making herbs and fruits grow in abundance. 香椿 (xiāngchūn – Chinese Toon), aromatic willow, prickly ash leaves, large coriander, tree tomatoes… The Dai people of Xishuangbanna are especially skilled with cultivating spices. Local women transplant fragrant wild plants and medicinal herbs from the mountains into their home gardens and daily use. For those who understand how to combine mountain plants into seasonings, this is the season of rich, aromatic harvests.

In winter and spring, cold winds from the Mongolian Plateau sweep toward the ocean, leaving the Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau dry and clear. These winds make possible Yunnan’s celebrated dried delicacies such as ham and cured beef. Whether in Nuodeng or in Xuanwei, those who can skillfully make ham must be unusually sensitive to the wind. They know when to take in the aromas carried by the monsoon and when to capture and preserve the fleeting freshness it brings.

Basking in the Sun

In Yunnan’s winter, people step outside to warm themselves in the sun, and food also needs its time with the light. Drying is a quiet celebration of harvest shared across courtyards, rooftops, fields, and roadsides. 乳扇(Rǔshàn-Milk Fan), fermented bean curd, dried eggplants, dried radishes… each carries the soft fragrance of sunlight. Open courtyards and pathways between fields become natural kitchens.

When Bai women make rushan, the milk is rich and fragrant. On clear days, they hang the cheese in the sun to dry. Through all seasons, sunlight becomes something that can be eaten. The Bai ethnic group is the 15th largest minority in China, primarily living in the Dali Bai Autonomous Prefecture in Yunnan Province.

Bai women hang sheets of rushan to dry. Rushan is a traditional Bai food made by adding hot papaya juice to cow or goat milk. The milk curdles and is shaped into fan-like sheets before being dried on a wooden frame. We pass an abandoned village house that has been turned into a granary where grains are dried in the sun.

In a time when ingredients can travel across the world at great speed, this land invites us to reflect. Beyond the rare or luxurious ingredients defined by markets, what touches us more deeply are the lives woven into each ingredient and every dish. True flavor cannot be separated from the gatherers, the mountains that nurture the plants, or the soil that shapes their character. Local cuisine carries meaning only when it preserves this connection between people and the land that feeds them.

Co-founder of Snout & Seek and FARLAND, ZhuangZhuang is passionate about understanding the local cultures of different ethnic groups through an anthropological lens. She aims to share the sustainable wisdom of these cultures with a wider audience through publications, products, and other methods. Zhuang enjoys photography, jazz music, cute animals, and Chinese traditional divination culture.

No spam, no sharing to third party. Only you and me.

Member discussion