Sweet, but Not Dessert: Yangshuo’s Language of Sugar

The way of enjoying not only sweetness, but blessings.

Sugar is not merely a taste, nor is it only a daily seasoning. Over a long stretch of history, it has intertwined with the multiethnic cultures of Guangxi, Central Plains traditions, and Lingnan influences, shaping a distinctive way of life in this region.

In French cuisine, dessert is a clearly defined course, served at the end of a meal as a moment of indulgence and closure. Historically built on sugar, butter, cream, and refined flour, dessert emerged in a context where sweetness was once rare and closely tied to wealth, leisure, and courtly culture. In contrast, many Chinese food traditions never separated sweetness into a final act. Meals were structured around grains and seasonal foods meant to sustain daily labor, with an emphasis on balance, digestion, and harmony rather than excess. Sweetness existed, but it came from fruits, grains, and natural sugars, and was woven into everyday snacks, festival foods, rituals, and offerings. What may appear from a Western perspective as the absence of dessert is in fact a different understanding of sweetness itself, one that values continuity, blessing, and balance over indulgence and display.

Sugarcane is an ancient plant. Although the French historian Fernand Braudel wrote in Civilization and Capitalism, 15th–18th Century that sugarcane likely originated along the Bay of Bengal between the Ganges Delta and Assam, research by the Chinese scholar Ji Xianlin shows that China began cultivating sugarcane as early as the Warring States period (475 BCE to 221 BCE). Historical records indicate that by the first century CE, the character “蔗” (zhe) was already used to refer to sugarcane, and wild sugarcane had appeared in Lingnan, eastern China, and western China.

Historical sources show that by the Sui dynasty, sugarcane cultivation in Yangshuo had already reached a considerable scale. Yangshuo, a county and resort town in southern China’s Guangxi region, was officially established in the year 1400, and by that time had become a multiethnic settlement. Even earlier, during the pre-Qin period, peoples collectively referred to as the “Baiyue” had already lived and merged here. Their descendants evolved into today’s Zhuang, Yao, Miao, Maonan, Mulao, and other ethnic groups, totaling eleven minorities in Guangxi. In the languages of the Zhuang, Dai, Shui, and Maonan peoples, sugarcane is pronounced the same way, “ten³,” meaning fresh, tender, and crisp. This description perfectly matches sugarcane’s flavor. The word for “sugar” did not appear only after sucrose was discovered. It originates from ancient Yue languages used to describe honey, a term that existed as early as the hunting and gathering era.

Sugarcane fields and freshly cut stalks

In Guangxi’s mountainous terrain, many minority groups historically settled at higher elevations for defensive reasons. These areas were less suitable for growing sugarcane than the plains and hills along the Li River, yet sugarcane has long been woven into daily life. Even today, when Zhuang families cook meat stews, they often add sugarcane or sugarcane juice to remove strong odors.

Sweetness and Pine Blossom Candy

Gifts for Ancestors and Life’s Milestones

Guangxi’s abundant waterways and history of cultural exchange shaped a sweet tradition influenced by both Central Plains pastries and Lingnan cuisine. Sugar cakes, taro cakes, radish cakes, pomelo leaf cakes, glutinous rice balls, mugwort cakes, mung bean cakes, and taro rice cakes are all part of this landscape. Some originated from minority traditions, while others flowed in from Guangdong.

Fried sugar cakes made with glutinous rice and sugar, and mugwort cakes

Both rural and urban families in Guangxi prepare sweet foods on Lunar New Year’s Eve to honor ancestors and welcome the Kitchen God. The twelfth lunar month and Spring Festival mark the peak season for sugar consumption. Sweetness, first discovered through honey, was once a rare and precious gift. To preserve it, people sought new sweet ingredients, and sugar gradually took on ceremonial and symbolic meanings.

In the past, sugar served as a matchmaking medium among Zhuang communities. The courtship stage was called “ting tang,” literally “placing sugar.” On the wedding night, sugar tea was served alongside celebrations. During festivals such as Spring Festival, Dragon Boat Festival, and Mid-Autumn Festival, sugar was indispensable. Winter also coincided with sugarcane harvest and sugar production, ensuring that even modest households could serve pine blossom candy and sugar cakes to guests during the New Year.

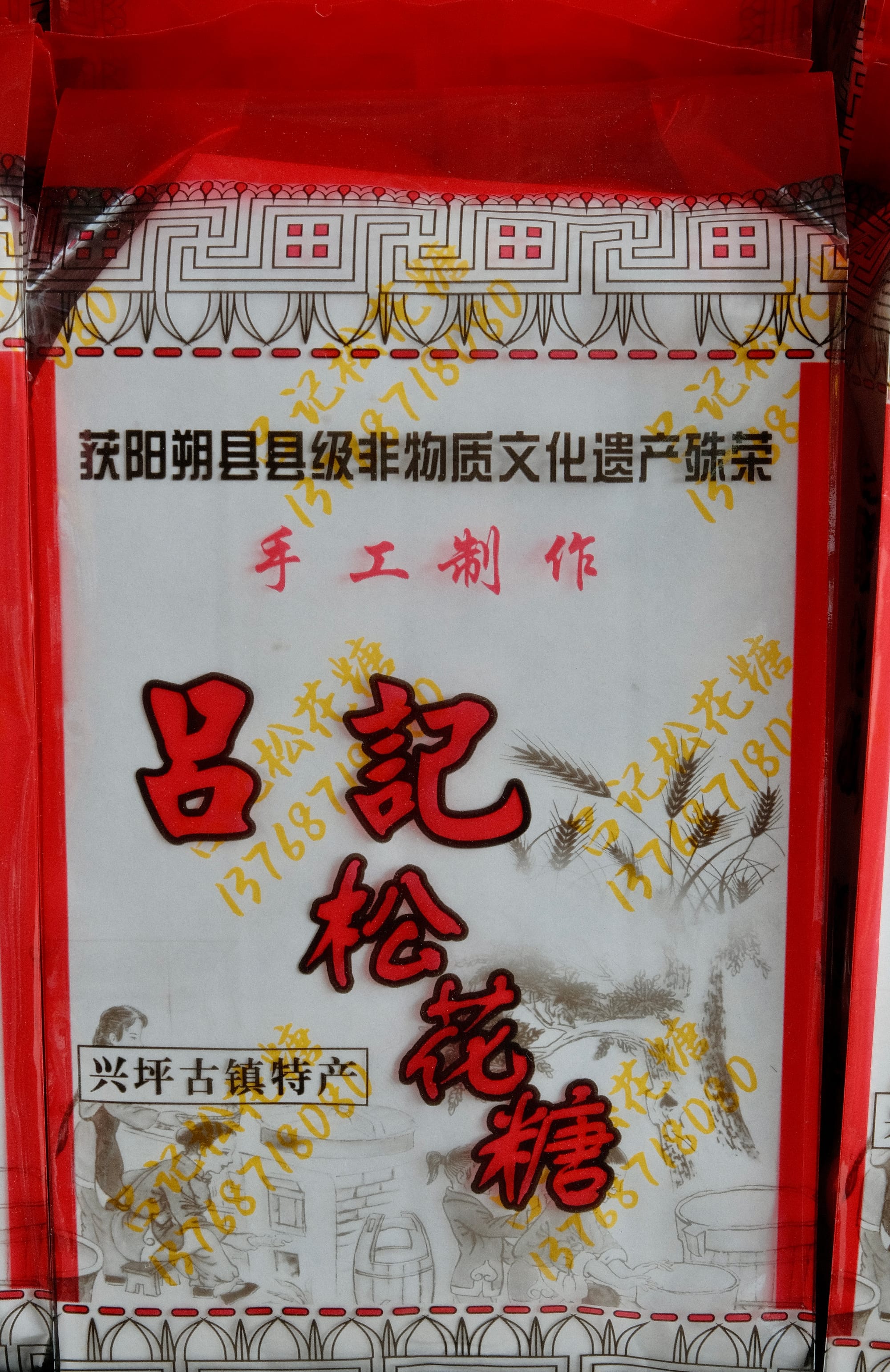

The history of pine blossom candy in northern Guangxi can be traced back to the tenth year of the Kangxi reign in the Qing dynasty. In Xingping Town near Yangshuo, two shops with over fifty years of history still preserve traditional methods of making it.

Pine blossom candy resembles sachima (a sweet snack in Chinese cuisine made of fluffy strands of fried batter bound together with a stiff sugar syrup) in appearance, but the texture is entirely different. Locals judge good pine blossom candy by how “loose” it is, meaning crisp rather than sticky. Achieving this depends on the crunchy rice pieces inside. Oil temperature, quantity, and frying time are all critical. One step, known as boiling the sugar syrup, requires constant stirring. If the syrup is too thin or too thick, it will not coat the grains properly, and the entire batch is ruined. Well-made candy reaches a texture closer to pastry than to caramel.

Left: cut pine blossom candy / Right: fried rice pieces in the mold to cool down

Although the process follows seven fixed steps, grinding, battering, mixing, rolling and cutting, frying, coating with syrup, shaping and slicing, each craftsman has their own techniques. This is why pine blossom candy varies from shop to shop.

In the past, pine blossom candy was an essential New Year purchase in Yangshuo and Guilin. Today, with industrial sweets everywhere, it is no longer considered rare. Most buyers are older locals. Pine blossom candy remains a daily tea snack, and at weddings, it still appears among the celebratory sweets. Many say that without it, something feels missing.

Traditionally packaged pine blossom candy and freshly fried rice crisps before syrup coating

Sweetness once reserved for festivals carries joy through dopamine release. This may be why humans have always treasured sugar and kept it in circulation.

Oil Tea and Sweets

An Everyday Comfort

Yangshuo’s oil tea tradition comes from Yao communities in Gongcheng County, over forty kilometers away. Winters in northern Guangxi are cold, and to keep warm, Yao people pound tea leaves, ginger, and garlic, boil them with salt, and serve a savory tea. The flavor is mildly sweet and spicy, rich with ginger and garlic. Though it originated with the Yao, oil tea naturally spread across villages and towns.

Sweet snacks and oil tea at a market stall, and oil tea being prepared

Locals often meet at oil tea shops to talk through matters of daily life. It is not just food, but a way of slowing down.

Every morning at the market, regulars sit on wooden benches at oil tea stalls. Without much conversation, the vendor places a stainless steel bowl filled with fried crisps, roasted rice, and peanuts, then pours boiling tea from an aluminum kettle. The tea must be scalding hot and is kept warm over charcoal. The crisps, made from brown sugar and glutinous rice flour, soak up the tea. Eating oil tea feels more like eating than drinking, spoon by spoon.

Oil tea accompaniments and people enjoying oil tea

People sit with friends they have known for decades, pairing sugar cakes with oil tea and chatting slowly. The tea is light, slightly salty, and faintly bitter, perfectly balanced by the sweetness of mugwort cakes. Some sit alone, talking with the vendor or simply watching the stall bustle. Elderly people, adults, and children alike find a moment of calm in a single bowl of oil tea.

Co-founder of Snout & Seek and FARLAND, ZhuangZhuang is passionate about understanding the local cultures of different ethnic groups through an anthropological lens. She aims to share the sustainable wisdom of these cultures with a wider audience through publications, products, and other methods. Zhuang enjoys photography, jazz music, cute animals, and Chinese traditional divination culture.

No spam, no sharing to third party. Only you and me.

Member discussion