Let Old Seeds Adrift Awaken the Earth

The domestication of wild plants and the practice of saving seeds mark the origins of agriculture. From that moment on, humans began collecting seeds from the crops they grew each year, storing them for the next planting season. Meanwhile, seeds that naturally fell into the soil adapted to the land’s specific conditions. They sprouted, flowered, and bore fruit according to the local soil and climate, allowing life to continue on its own terms.

This cycle, repeated over thousands of years, embodies the accumulated wisdom of human agriculture. Over time, old seeds continued to evolve, coexisting with their surrounding environments and adapting to local ecosystems through long years of evolution.

After living in the city for many years, even though I grew up in the countryside, my standards for judging the quality of fruits and vegetables have gradually narrowed. I now mostly worry about whether they contain excessive pesticides. I rarely cook on weekdays, and vegetables ordered through grocery apps often sit in the refrigerator for a week or more. When even freshness cannot be guaranteed, eating seasonally or tracing food back to its original flavor feels like a luxury.

To understand the connection between the quality and the availability of the vegetables we see in our homes and stores, we interviewed Wang Suman, an avid seed researcher based in Chengdu, in her studio filled with old seeds. She explained to us in detail what old seeds mean to us in the modern world.

Wang Suman has spent more than a decade working with old seeds, quietly building a practice that sits between agriculture, ecology, and cultural preservation. Through fieldwork, seed collection, and long term collaborations with farmers across different regions, she focuses on conserving traditional crop varieties that are rapidly disappearing from everyday farming. Rather than treating seeds as static specimens, she believes they must continue to be planted, grown, and exchanged in order to stay alive. Her work centers on what she calls “living conservation,” allowing old seeds to adapt, evolve, and rebuild relationships with the land and the people who grow them.

“These original old seeds are disappearing very fast,” Wang Suman said with a sigh. “At this point, the rice varieties we can still trace number only a little over a thousand.”

With ten years of experience in old seed conservation, she speaks from a state of deep concern. China is one of the birthplaces of rice cultivation, with a history spanning several thousand years. In the 1940s alone, there were more than forty-six thousand varieties of rice. Almost every village had its own rice, and every rice had its own unique flavor.

In my rural hometown in Luzhou, the winter cabbage we eat comes from our own garden. It is a local variety with many leaves and very little stem, sweet in taste and low in fiber. Yet in Chengdu supermarkets, the only option is a uniform, golden cabbage with thick stems and few leaves, bland in flavor and unpleasantly fibrous. As a result, the star of the kitchen has quietly shifted from ingredients to seasonings.

On the phone, my parents often say, “What do people in the city even eat? Vegetables don’t taste like vegetables, meat doesn’t taste like meat.” I find myself unable to argue, only adding that people living in the city really do eat terribly. During holidays, our relatives living in the city always load up their car trunks with vegetables from the family garden before returning home. They choose whatever is in season during spring and summer, but in autumn and winter they always bring pumpkins, sweet potatoes, and radishes back with them. These are the most common vegetables in supermarkets, yet the locally grown flavors are completely different from what city life offers.

Biology often tells us that “a species is a gene pool.” Old seeds in nature serve as the genetic source for hybrid seeds. The richer the genetic resources, the greater the potential for hybrid vigor. Yet today, as hybrid varieties are widely promoted and planted, conservation efforts cannot keep pace with the speed of endangerment. Farmers are saving fewer and fewer seeds of their own. Old seeds in nature are disappearing at an accelerating rate, and humanity’s range of choice is shrinking rapidly.

Farming is a profound field of knowledge. What seeds should be planted in what soil, and at what time of year, and much much more, were things farmers in the past understood clearly.

“Many species in China have been able to survive for thousands of years because farmers mastered the ability to purify and domesticate seeds,” Wang Suman explained to me. “In the past, farmers practiced meticulous cultivation. They constantly selected and bred superior varieties.”

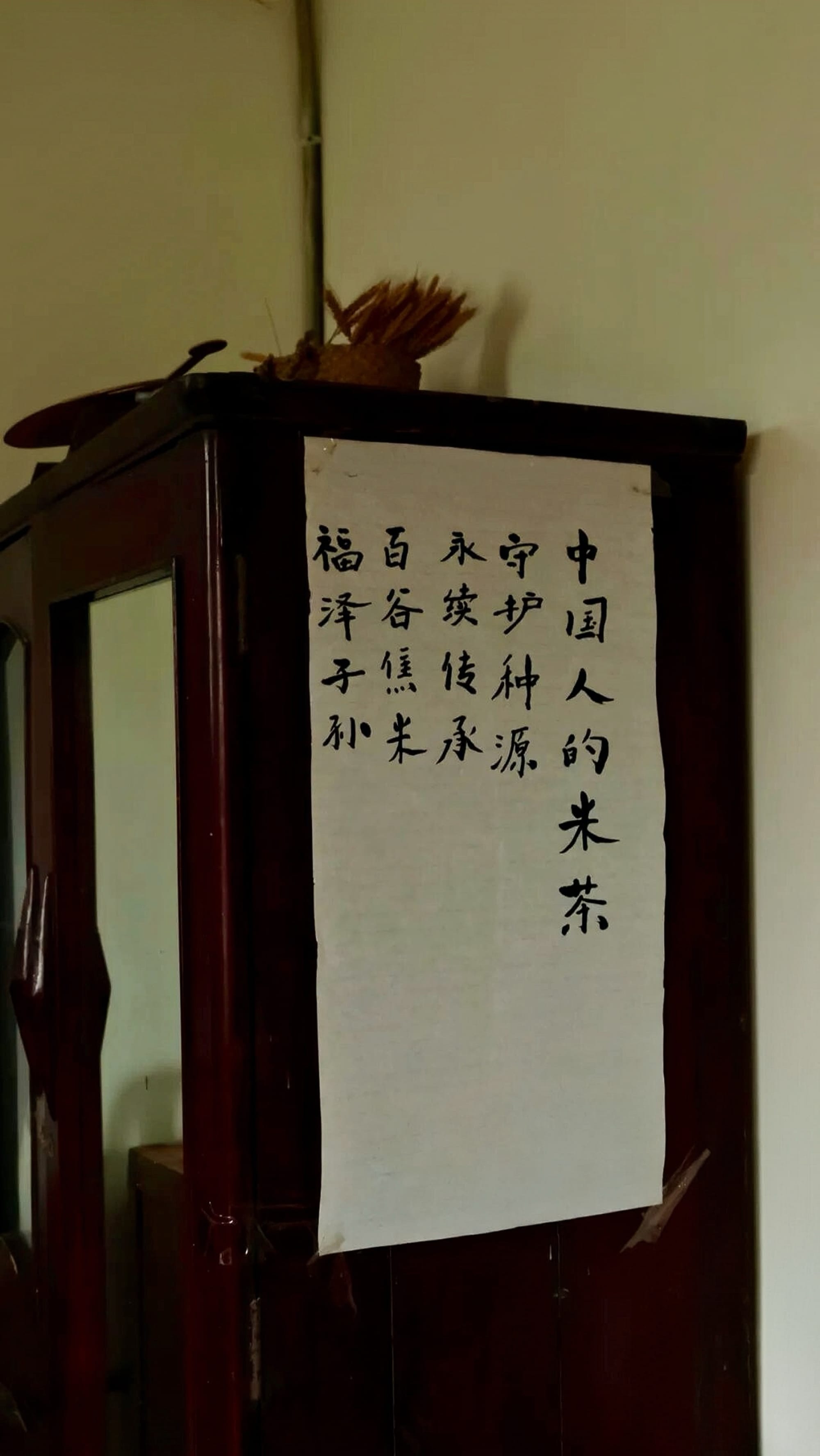

A corner of the studio, the words on the paper writes: “Rice tea of the people, protecting seeds, sustaining abundance, and blessing generations to come”.

Selection and breeding were essential in traditional agriculture. They were the decisive factors in maintaining the vitality of old varieties. Wang Suman describes this process as “purification and domestication.” Each year, farmers selected seeds from plants with the best overall traits, including yield, quality, and disease resistance. These seeds were then replanted, allowing them to continuously adapt to local environmental conditions and grow stronger through natural competition over generations.

With healthy seeds and organic cultivation methods, the quality and yield of old seed varieties can gradually improve. This not only meets human survival needs, but also contributes to better health.

Today, reliance on ready made hybrid seeds from seed companies has caused farmers to lose the practice of selecting and breeding local old seeds. At the same time, the excessive use of greenhouses, pesticides, and chemical fertilizers has weakened crops’ natural disease resistance. Over time, both ecosystems and agricultural systems become increasingly fragile.

Of course, in response to species extinction and seed crises caused by war or natural disasters, more than 1,700 seed banks now exist worldwide. Institutions such as the Millennium Seed Bank in the UK, the Svalbard Global Seed Vault in Norway, and the Southwest China Germplasm Bank of Wild Species collectively preserve over twenty-four billion seeds.

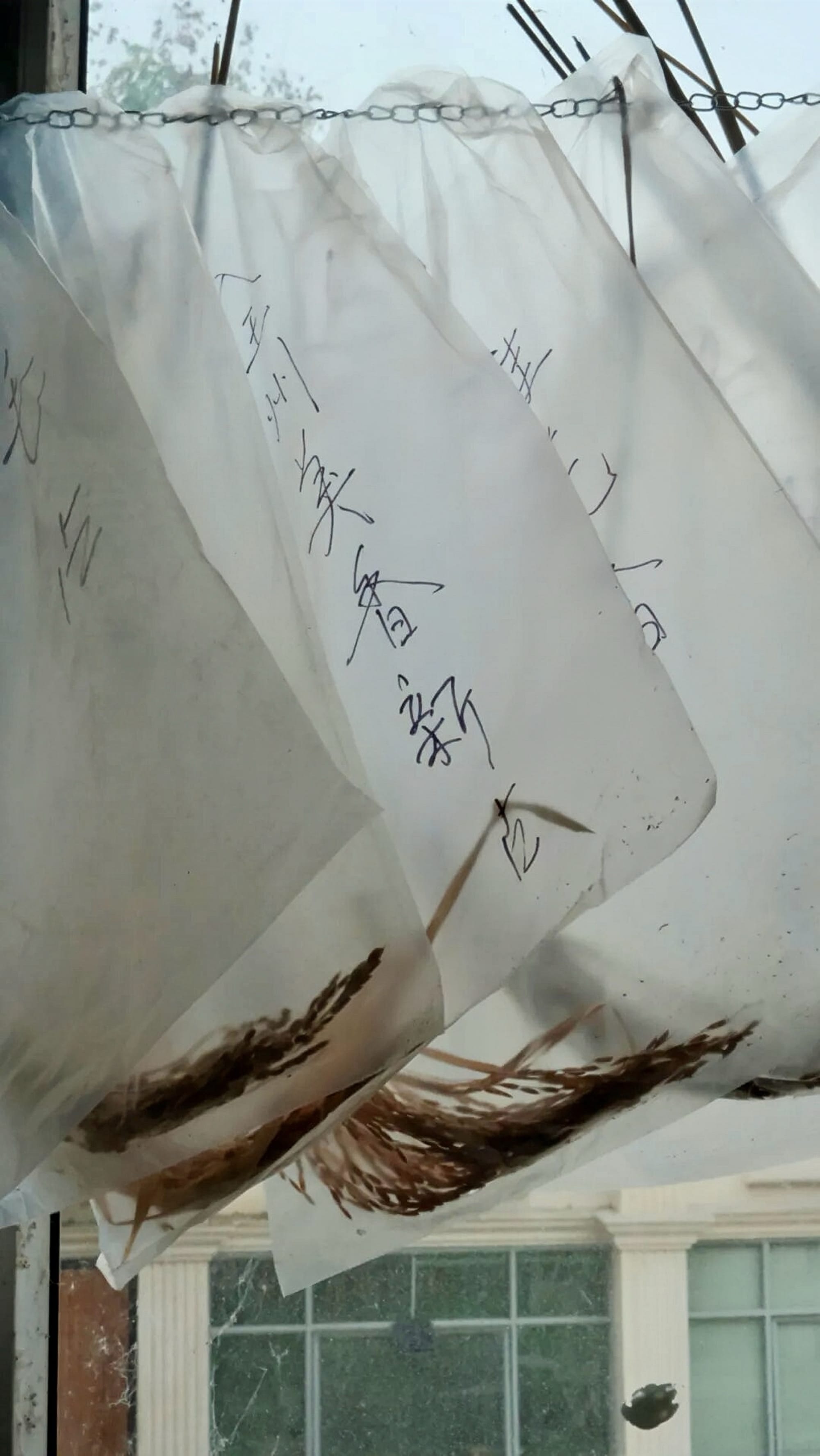

“Seed Drifting” is a seed conservation platform founded by Wang Suman. It serves as a complementary approach to official seed banks. Through this platform, old seeds collected by the team are sent out to farmers in different regions. Those who successfully plant them send new seeds back the following year, allowing conservation through continued cultivation and circulation.

“Each species is connected to around twenty-five other species,” Wang Suman explained. “If one disappears, other species along the chain will disappear as well. On the other hand, if an old seed is planted in a suitable ecological environment, the organisms associated with it will follow. After two or three growing seasons, its community will be rebuilt.”

While my own understanding was still limited to the idea of protecting food security, Wang Suman emphasized something broader. Old seeds have the power to repair and reawaken ecosystems. This perspective offers a reverse way of thinking about biodiversity and provides another explanation for the resilience and risk resistance of old seeds.

A travel planner and writer at FARLAND, Juan specializes in crafting immersive travel experiences and compelling narratives that bridge culture, adventure, and local authenticity. Lover of sports, cooking, nature and the pursuit of love.

No spam, no sharing to third party. Only you and me.

Member discussion