From the Iberian Peninsula to the Yangtze Plain: How ham thrives in two worlds

Before I learned about Jinhua ham, I didn’t really know how it was made. The only thing I was sure of was its reputation, it’s widely considered one of China’s finest hams. Even though I was born and raised in China, I’d never had many chances to eat it, let alone taste it with any attention.

Compared with Jamón Ibérico from Spain or Prosciutto di Parma from Italy, Jinhua ham is far less known outside China, even though its craft is just as rooted in time, salt, and place. Since we moved back to China two years ago and settled in Shanghai, we’ve been visiting food producers across the country, trying to understand how they respond to fast-growing and ever-changing markets while still holding on to the traditions that give their products a soul.

In early 2023, I spent three months in Spain studying at Le Cordon Bleu's Madrid campus. That was when I first really encountered Spanish ham up close. It’s everywhere in Spain, widely available in supermarkets, and priced by grade, from everyday packs to hams treated like heirlooms. It’s so woven into daily life that you see it in every setting, from fine-dining restaurants to airport sandwich counters. Whenever I speak with Spanish friends about food, they’re unmistakably proud of their ham.

Spain is also probably the second place I’ve seen such deep affection for pork, after China. But the relationship is different. In China, shaped by a long history of cooking with fire, people tend to cook everything, and many are not drawn to foods that feel “raw”. That’s part of what makes Jinhua ham distinct from Jamón Ibérico or Prosciutto di Parma. In Chinese kitchens, it’s used less as a ready-to-eat delicacy and more as a powerful source of umami, added to soups and stews to lift the whole pot. You don’t typically eat Jinhua ham raw, at least not yet.

Fascinated by Spanish ham, I became obsessed with the details, how carefully the pigs are fed, and how tightly the process is governed by rules and technique. That curiosity naturally led me back to China: I wanted to understand how Jinhua ham is made, and what “tradition” looks like when it’s produced at scale today.

So when a friend mentioned she knew a company making Jinhua ham, I asked her to introduce me right away. Thanks to their generosity, we were able to visit the factory and see their modern production up close, the technology they use, and the disciplined routine that allows them to produce consistently, day after day.

We also tasted something new: their experiment with ready-to-eat, raw-style ham designed for Chinese consumers. It was an eye-opening visit, and I’d love to share this journey with you.

Even though I had already watched the company’s promotional video and read their introduction, what greeted me at Huatong still surprised most of us. With Mr. Fu, the friendly head of production, as our guide, we were taken into an area that isn’t open to the public.

First came the hygiene routine. We were given white lab coats, hair nets, and rubber boots, then directed to a handwashing station that felt straight out of a medical drama. You turn on the tap with your foot pedal, right under the sink, and the full cleaning procedure is posted on the wall in clear steps. And it doesn’t stop at hands: before entering, you’re reminded not to forget your boots. The last step is to walk through a shallow sanitizing footbath, the kind you sometimes see at the entrance to a swimming pool, before you’re allowed further inside.

I wasn’t sure what I expected before entering the facility, but it definitely wasn’t this. With three plants operating at the same time, we stepped into one of them and found ourselves in a space that felt unexpectedly vast, almost empty. For a moment, I couldn’t even tell where the ham was. Before I could ask, Mr. Fu began his introduction.

Huangtong is a pork company from start to finish. They raise pigs, process meat, and manage the entire chain in-house. With fresh supply at their fingertips, they handle a large volume of pork legs every day, the starting point for making Jinhua ham.

Then the tour shifted from introductions to a mind-opening lesson. Behind each heavy latch along the corridor was a vast room, tightly controlled for temperature and humidity. Door by door, we were able to follow Jinhua ham from its very first steps all the way to its finished form.

This seemingly empty space actually traces back to 2008, nearly twenty years after the company was founded, when this workshop was built and put into operation. The plant is equipped with three Italian production lines, with an annual capacity of up to 800,000 hams.

They work with both fresh and frozen pork legs, but the first steps are the same: before any salt touches the meat, each leg goes through a mechanical “massage” that relaxes the muscles and presses out residual blood.

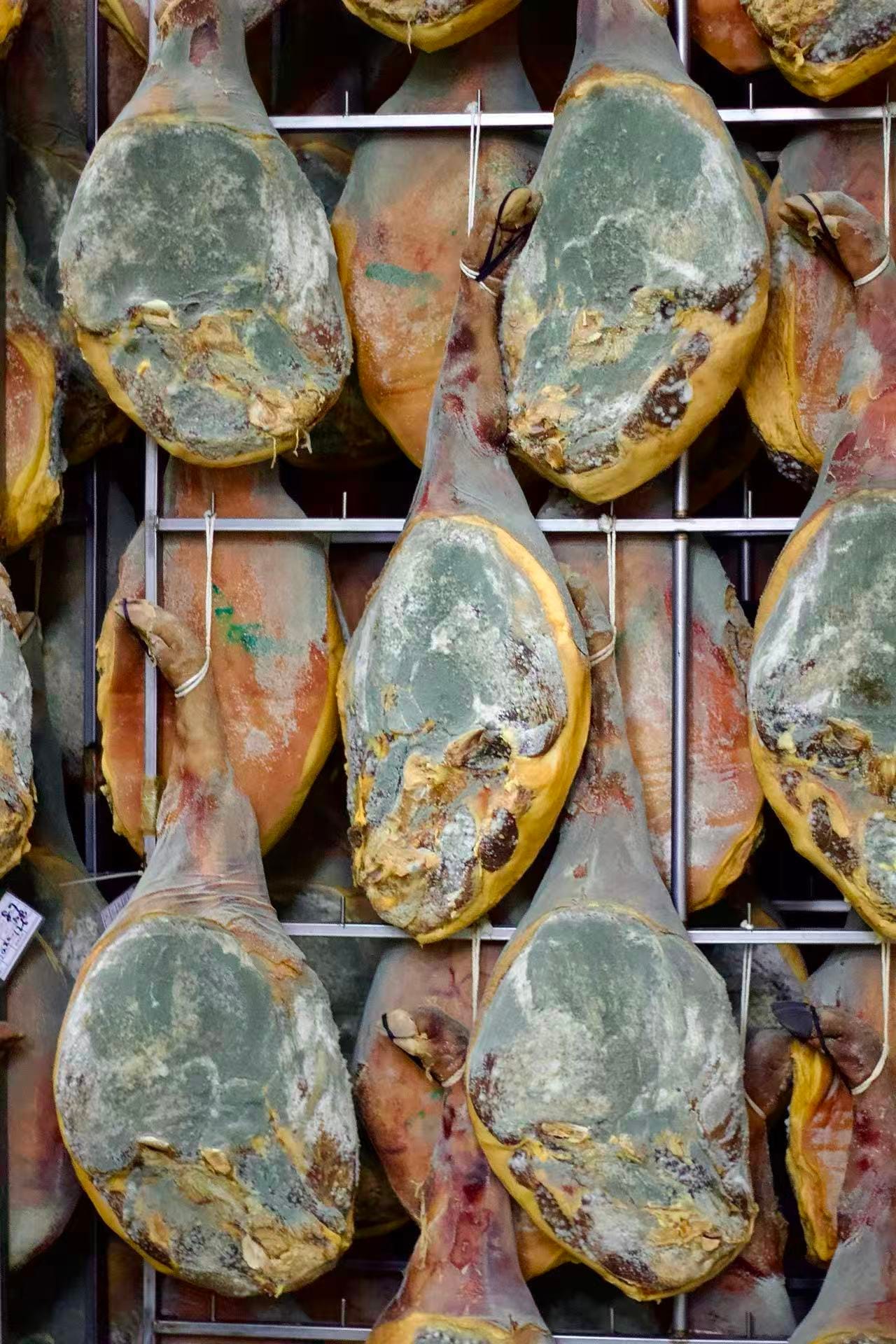

After salting, the legs move into a carefully managed air-drying phase at around 3–5°C, with humidity kept between roughly 55% to 90%. Airflow is intermittent rather than constant, because too much wind dries the surface too quickly and can cause cracking. One drying room alone can hold more than twenty thousand legs, a number that’s hard to grasp until you see the hanging rows in person.

From there, time takes over. After air-drying, the hams are left to naturally ferment for about two months, developing a faint lactic aroma. They’re then high-pressure washed to remove surface salt and the proteins that have seeped out. A warmer drying step follows, along with a one-week transition period, before the hams enter high-temperature fermentation. This is where the factory’s control systems really show: the goal is to draw out aroma and speed up protein breakdown through three temperature stages, roughly 18°C to 33°C, with two longer phases of about three months each and a final shorter phase of around two weeks. Because temperature and humidity are tightly regulated, the process avoids the old uncertainty of “relying on the weather.”

Near the end, the hams are encouraged to grow beneficial mold, which helps further break down proteins while reducing moisture loss. The mold is introduced through natural inoculation, supported by Jinhua’s long history of ham-making and its spore-rich air, before the legs finally mature into the finished product.

At that point in the tour, I finally asked Mr. Fu the question that had been sitting with me the whole time: “What’s the difference between Jinhua ham and the kind of ham you can eat raw? And if you already have the technology, why not make more of it?” He paused, his expression hard to read, as if he was sorting through the best way to answer.

“It’s true,” he said. “With our current machinery and controls, we can make ham that’s ready to eat. In many ways, our process is already similar to what you’d see in Italy or Spain. The problem isn’t technique. It’s the market.”

That was the moment I realized how small my own perspective is compared with the vast majority of people in China. Jinhua ham, for most households, isn’t something you slice and eat on its own. It’s a source of xianwei (鲜味), the deep savory lift that transforms a pot of soup or a slow stew. And for most Chinese diners, cooked dishes, especially soups, are still the everyday norm. Even as more people become curious about Western food, that openness is still concentrated in big cities. For many, the idea of eating meat “raw” remains a boundary, and in some cases, a taboo.

After the tour, we sat down to a banquet lunch where pork showed up in a dozen different forms, each dish making a different point. Huatong has even created its own Jinhua Ham Hot Pot: cured ham is used as the base flavor for the broth, and you build the pot with vegetables and proteins as you go. The soup was unbelievably delicious, rich but never overpowering.

The highlight, though, was an experimental ready-to-eat ham they used to make. It reminded me of Ibérico, with a deep, nutty fragrance and a restrained salinity. The texture was silky, and the aroma lingered long after each bite. If there’s ever a moment when I wish taste could travel through a screen, this was it. They don’t sell it anymore, so we had to savor what we had on our plates.

Moments like this also make me think about how unforgiving the market can be. It decides what gets scaled up and what disappears. Who knows how many beautiful flavors have been abandoned, not because they lacked value, but because they didn’t fit what was considered “mainstream” at the time. The story of Jinhua ham continues through the people who hold tight to tradition, but it also grows through companies like Huatong that are trying to push the craft forward with modern methods. I like to believe that one day I’ll see their ready-to-eat ham on shelves, and until then, I’m happy to be one more voice rooting for it to come back to life.

A Tianjin, China native - Chloe has a deep appreciation for all things hotpot. Her appreciation of food and culture runs so deep that after a successful corporate career, she decided to uproot her life in China to attend Le Cordon Bleu Ottawa and Madrid. After working in the culinary industry in Canada, she decided to found Snout & Seek!

No spam, no sharing to third party. Only you and me.